Old Interview for the Inside Hockey Magazine

September 22, 2003: Arthur Chidlovski

Old School: Perspectives from another land…

By Mike Wyman (Canada)

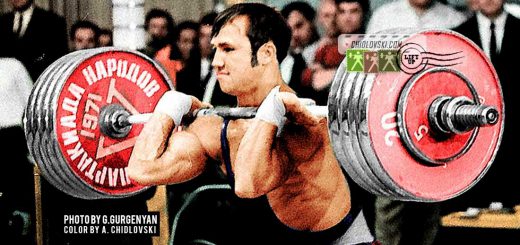

Arthur Chidlovski is a 39 year-old hockey fan who has lived in Massachusetts for the past decade, where he works in information technologies. He has also been a comedy writer, journalist and competitive weightlifter.

Born in Moscow, he is a lifelong hockey fan and graciously agreed to cast an eye back to his childhood and share some of his memories. It’s not every day that the chance to speak with someone who cheered for the “wrong side” in 1972 comes along.

Chidlovski became a hockey fan in the years that television was replacing radio as the major mass-media. Nikolai Ozerov was the voice of Soviet hockey, remembered in Russia much the way Foster Hewitt is in most of Canada.

“Ozerov was the number one broadcaster. He was funny and very entertaining. The people just loved him. Later on we got commentators who were former hockey players or sports personalities. They knew sports from A to Z but they couldn’t present it like Ozerov. He was down to earth and didn’t drop inside terms that we didn’t know. Sometimes we even felt smarter than him.”

From Ozerov’s broadcasts, young Arthur learned that Bobby Hull wore a wig and that Gordie Howe forced his sons to play hockey, the better to exploit them. Most of his information on the NHL came from a weekly magazine named Football/Hockey; a functional title for a journal devoted to the two most popular team sports in the USSR.

“The most stereotypical picture of Russia is a whole bunch of Russians wearing fur hats standing in a line. I still remember that I had to get up every Sunday at 5:00 in the morning and go stand in line at the newsstand to get this Football/Hockey weekly. It was impossible to get it in the stores so you had to go early to get it. You mingled with your linemates – not your teammates but the other guys in the line.”

“It was the source of most of my information, especially about North American hockey. The NHL was mysterious and far away. I read in the papers that the Soviet players idolized the NHL players. Dryden, Esposito and so on and so forth but I think it was an exaggeration because we didn’t have any information about the NHL teams. We heard the names but we probably couldn’t have told you what team they played for. It was part of the propaganda. They really didn’t cover the NHL.”

The main competition in the Soviet mind was the one between the USSR and Czechoslovakia.

“Before 1972 I was a traitor. I was a Czech fan. They were a lot more flexible than the Russians were. The Russians were mostly playing an offensive game. Defence and goaltending were secondary. The rivalry between Russia and the Czechs was mostly a rivalry between a student and a professor. We learned the game from the Czechs and at some point the student surpassed the teacher. The Soviet invasion of 1968 just added to the rivalry. It was a way for them to speak up because they couldn’t resist against the tanks and the military force so they just did it on the ice.”

Centre of the hockey world, Moscow was home to three top teams. Red Army, Dynamo and Spartak all called the capital home. In the decades before licensing agreements saw virtually every fan decked out in authorized merchandise, a fan’s allegiance could be easily determined by a quick glance at his scarf. Red and blue indicated a Red Army supporter; blue and white were the Dynamo colours while Spartak fans decked themselves out in red and white neckwear.

“There were three aces in Moscow in the 1970s. There was Valery Kharlamov, who played for Red Army, Alexander Yakushev, who played for Spartak and Alexander Maltsev, who played for Dynamo.

Allegiances were serious matters in that time and place. They were often forged early as well. In those days, competition was intense to get into a good program. If a kid wasn’t picked up by a school affiliated with one of the powerhouse squads by his teenage years odds were he didn’t have a future in the sport’s upper echelons.

While most of Chidlovski’s buddies were Red Army fans, he wore the blue and white colours of Dynamo Moscow when he went to the games. He also tried to try out for the Dynamo-sponsored organization as a youth. Turns out, it just wasn’t meant to be.

Beer and hockey have a bond that transcends cultures and distances. Arthur Chidlovski was one of hockey’s youngest alcohol-related casualties.

“I didn’t even make it to the ice rink,” he remembers. ” On my way to the audition there was, right next to the Dynamo ice rink, a dark place, a beer garden. I don’t know if the fans worked but they were always there discussing the latest game and debating who was the best player.”

Arthur was stopped and asked who the best player in Russia was at the time. Unfortunately he named his favourite player, Helmut Balderis, who had the misfortune of suiting up for the cross-town Red Army side.

“I got a punch in the nose. They broke my nose and then told me that the right answer was Alexander Maltsev.”

Chidlovski never made it to the ice, turning to weightlifting a few years later.

Talk turns to the 1972 Summit Series and Chidlovski’s discovery that the NHL game was not exactly as it had been portrayed in the Soviet sporting press. As he had said earlier, his knowledge of the game on this side of the Arctic Ocean was spotty at best and often took second place to his native country’s perceived superiority.

“Going into 1972 we had nine consecutive World Championships. We knew that we were the best in the world outside Canada. The NHL was presented in the media as if it was an extreme sport.”

“When I was a kid, before actually seeing a game, my impression of the NHL was that it was sort of like ancient Rome. Gladiators on the ice with the announcer saying ‘Ben is now fighting Jerry and the fans are turning thumbs up or thumbs down yelling ‘Kill him Ben’ and ‘Kill him Jerry’. When we finally got to see a game, it changed our perspective completely.

Yvan Cournoyer was an instant favorite in the Soviet Union. It started when his name was translated as Ivan, spawning rumours that he was of Russian origin. While he may have been a French-Canadian, it was obvious that he had Russian parentage according to Soviet reports. His speed and skating ability seemed to lend credence to the theory. After all, if he wasn’t Russian why would his parents named him Ivan? Cournoyer was soon nicknamed Vanya, the Russian equivalent of Bill, and is to this day one of the more popular NHL Alumni in the land of his purported ancestors – both for his bloodlines and the way he played.

“He was one of the players we all loved. He played a very good Euro style.”

One image that stuck with Chidlovski through the years was Alan Eagleson’s notorious, and it turns out not cross-cultural, middle finger salute, given as he crossed the ice in Moscow. In an interview after the game the noted jurist and future convict was asked what the hand gesture meant. It should have been a clue to the world at large when he told a Soviet TV audience, through an interpreter, that it meant the number one.

In 1991, when Chidlovski arrived in America, he was asked if he had any baggage to declare.

“Just one suitcase,” the new arrival said, combining it with the extended middle digit that Eagleson assured a nation was a simple singular number. In a concession to détente, probably after great debate, Arthur Chidlovski was admitted to the land of the free despite his inadvertent rudeness. He has since learned a lot more about American idioms.

Chidlovski, while not a member of the elite, attended school with a number of children of important people. One was the son of the Ozerov family physician. Through a combination of luck and perseverance, he was able to parlay the friendship into admission to the second Canada-Soviet series.

“When Team Canada ’74 came to Moscow for the summit, they got free tickets from Nikolai Orozov. I said ‘I want a ticket too’.

“We can’t do it because we’ve only got three tickets.”

“I went down to the game with them hoping to at least get some autographs or maybe a ticket on the black market because you couldn’t get them at the box office.”

“They got their tickets from Ozerov and he said ‘Who is that?’

‘He’s our friend.’

“He looked at me for a few seconds, eye to eye. It must be a very Russian thing because here in the United States people prefer not to look at each other that way. He looked into my eyes and he said, ‘What’s your name, boy?’

‘Arthur Chidlovski.’

‘You know what, Arthur Chidlovski? You’re a lucky man. I have an extra ticket for you.”

Chidlovski remembers Ralph Backstrom as the best Canadian player. Another standout was Jean-Claude Tremblay.

“I was very impressed. He was so good and so clean. He was past his prime but so very smart. He wore a helmet too.”

Some 20 years later Chidlovski was employed by Soviet television and met the famed announcer once again. Ozerov laughed when the now adult Chidlovski told him the story of the extra ticket and said that he was glad he’d been able to introduce someone to the game.

In Chidlovski’s final years in the Soviet Union, hockey players began opting out of the Soviet system. First a few at a time, then the trickle became a flood as leagues in Europe and North America came calling, offering all the advantages of a consumer society that most Russians were now aware existed beyond their borders.

“Defections were happening in the 60s and 70s but it was usually circus performers, ballet dancers and artists. Hockey players were pretty hard-core people. They just didn’t do that. When Mogilny defected in 1989 he was a lieutenant in the Soviet Army. I guess it was just a generational thing.” Chidlovski theorizes.

He then recounts an anecdote from the 1972 series, a time when defection was not given the slightest thought by Soviet players.

“Vladimir Shadrin once told a story about how, after the fourth game in Vancouver, Alan Eagleson visited him and Alexander Yakushev in their hotel room. He also invited Tretiak and Kharlamov. The whole meeting was Russian-style with lots of vodka and caviar. After a couple drinks, Eagleson just asked them directly, ‘ Whattaya think, guys? How about playing in the NHL?’

“Tretiak answered, tongue in cheek, ‘The only way I’ll play in the NHL is if Leonid Brezhnev gives me his personal permission to do that.’

“As soon as Eagleson left the room they all started laughing. It was the most idiotic answer that Tretiak could come up with at that moment. None of them got a chance to play in the NHL.”

Chidlovski doesn’t foresee great things for hockey in Russia in the short term. Since the fall of collectivism, things haven’t been going well for his favorite sport. In recent years he has seen an influx of money into the game, bringing with it a number of foreign players, many from North America. Some fans aren’t too fond of outsider coming to take jobs away from Russian boys.

“We’ve got our own Don Cherrys in Russia who say ‘Why do we need all of these Czechs and Canadians if we have our own players?'”

The truth of the situation, in Chidlovski’s mind, is simple.

“We don’t have any players. The kids who are being drafted into the NHL these days were all born in the early 1980s. They started under the Soviet system. The 1990s were a disaster for Russian hockey.”

He fears that the crunch will come in a few years, once the supply of youngsters trained under the old regime runs out but he nurtures a small seed of optimism for hockey in the old country.

“I hope it’ll get better. They’ve got some money now and with Slava Fetisov as minister of sport…”

Arthur Chidlovski maintains and updates websites dealing with both the 1972 and 1974 Canada-Soviet series. They are well worth a look-see…